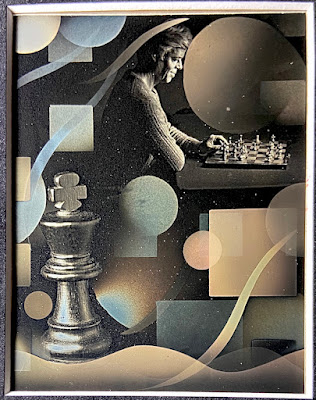

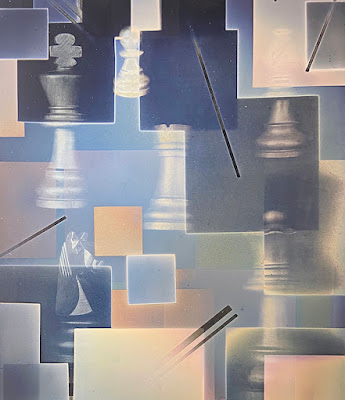

Daguerreotype Chess Series

During the summer of 2021, I found my interest for the game of chess revived with a new sense of vigor. I learned the game as a child in Russia, but haven’t played much in the last two decades. Early roots of chess stretch back 1500 years, and the game is simultaneously poetically elegant and surgically precise. Throughout history, chess was often used to teach military tactics and to aid in development of strategic thinking. With seemingly straightforward universal rules, it offers each player’s creativity room to develop a deeply personal style. There is also an element of art in a well-executed chess game; it is a thing of pure beauty, akin to an imperial Faberge egg. The more I played recently, the more I realized that the game of chess in many ways parallels the art of making daguerreotype images. In order to yield timeless results, both operations rely on planning and high degree of precision. While both pursuits have rather stringent and limited rules, both offer an absolutely infinite range of possibilities achievable with same starting toolkit, and a good result in both is a manifestation of skill level of each individual artist of player. Of course the game of chess is played against an opponent, and it is a battle of two minds. The process of making a daguerreotype is a solitary pursuit, where one uses skill combined with imagination to battle natural elements like humidity and light and to build silver particles in just the right way to distill and translate a beautiful ephemeral vision or idea.

There’s one key difference between chess and daguerreotype that deserves a closer examination; it was in fact that difference that inspired me to start making modern daguerreotypes in ways varied from tradition. Checkmate positions are quite self-evident, while an uninspired poorly made daguerreotype takes quite a bit of extra thinking to recognize. The game of chess evolved over fifteen centuries, and is more popular today than even. New approaches to strategy have had plenty of time to sprout, organically replacing the old ways because they led to winning positions on the board. Today, the sophistication exhibited by the top players is truly masterful, and the level of play is still constantly progressed. Millions of people around the world play chess and keep sharing and building communal knowledge. On the other hand, fewer than twenty people today make contemporary daguerreotypes on at least somewhat consistent basis. During the 1840 and ‘50s, when daguerreotype reigned as the supreme photographic method and tens of millions of images were produced, strong competition demanded photographers to pursue higher and higher quality outputs. Some 19th century artists sought ways to make their images have personal innovative styles, and a few intriguing explorations into artistic realms were indeed made by those rare individuals. However, a combination of several factors played a role in those early bursts of innovation not being pursued to their fullest possible extent: the short period during which daguerreotype method was practiced before being replaced by a cheaper and easier collodion method, the overwhelming mass demand of the time for purely representative images, the fact that serious discussion of photography as an independent art form was yet naturally in its infancy. All that and more resulted in this incredible medium being basically frozen in time. It is by no means easy to make a perfect representational daguerreotype in the ways of the old masters, and so most who attempt to do so today simply strive for those results, reaching happy homeostasis once a certain level of consistency has been achieved. Even the most adventurous contemporary daguerreotypists of today are simply revisiting the century-old ideas of abstraction, or simply going for larger and larger image surfaces. It is as if the status quo of daguerreotype method has been established in a simplified form; it seems that given a chessboard most are happy to stick to checkers.

While chess is a very Zen activity, photography has always been the fuel to my passion for life. I play chess as a hobbyist and don’t expect to ever draw a game against Magnus Carlsen, but looking for ways to take my images to the new heights, ones yet unimagined and unexecuted by anyone, is a constant insatiable urge. Incredulous at what vast uncharted territories are still left untouched within the daguerreotype medium, I continually express my experience of existence through art. These seven images were conceived and executed in order to highlight the relationship between the infinitely complex and beautiful worlds of chess and daguerreotype.