Having now finalized work on this series, I will attempt to put into words its impetus, as well as how it came to fruition. This will be a lengthy entry, proportional in size to the monumentally significant nature of this work for me, and therefore I shall start from the beginning, as all things have their origins.

In mid October 2018, a somewhat local man, known to himself and some others as a photographic artist, stopped by my studio. He was seeking a daguerreotype of his own likeness to be made by me; this was something he has been after for quite a while at that point. I should note that the very notions of artistic craft and photographic knowledge are deeply personal to me; it is something I revered all my life and was taught to respect. This meeting proved to be most disturbing though. It was one that brought me face to face with a professional socialite and opportunistic dilettante of archetypal proportions, who exuded brazenly self-satisfied disregard for even the very basic principles of photography. After failing to deliver anything of value in terms agreed upon, and before mailing back his portrait, the other party went to considerable lengths to physically destroy the image, destroying with it my silver plate, upon which multiple impressions could have otherwise still been secured. Seeing that precious metal surface obliterated by such deeply talentless hands, hands controlled by such an unimaginatively simple mind really stung, and I did succumb to a mild depressive episode for the next few weeks.

In a way, depression is part of fantasy world. To oversimplify a bit, it is that time when the mind gets lost in so many layers of hopelessness, that it gets confused, zeroes in on gloom, and seizes to see hope and brighter side of life. A depressed mind can often fantasize in ways that normally it would not. A lot of those fantasies of course lean toward negative thinking, but not all of them, and those are the ones I tried my best to pay attention to. Best way I’ve found to climb out of the vicious self-deprecating spiral is to pick the less tormented moments, and tune to that sometimes quietest of all voices, a voice of hope and inspiration, and then try to amplify it. Listened to carefully and long enough, some delightful bits of vibration can be decoded, a message that always pushed me to try and interpret it through tones and shapes in my images. This time around, the message I decoded was vague, but much more powerful than ever. A new certainty emerged that reinvention of my vision, of my work, and of daguerreotype process as known thus far were calling me from around a distant corner, and that this corner demanded to be rounded gently and methodically.

In mid November, I felt the overwhelming urge to pick up my buffing tools, and let the journey begin. With the subject of my first few plates I needed to say goodbye to those vacuous characters who pillage and pilfer artistic minds with their mindless dribble, undermining faith in larger purpose of Art. I say no, true art exists well outside the circles in which those characters rotate comfortably, lulled with cheese and wine, where sober scrutiny of quality and merit are shunned in favor of networking opportunities in search of larger and larger walls to cover.

Working obsessively and intuitively, I knew I was seeing but steppingstones of a new learning curve. There was something strong yet ephemeral though, a lingering mirage on the horizon of all my previous knowledge, and it was tugging and luring me forward. Was it something I read, some mistake I once made that maybe wasn’t a clue, something I heard someone say a long time ago, or was it the space left when they said nothing? This palpable tension of yet unrealized potential pushed me fume plates daily for close to two months. I took all the bits and pieces of my knowledge and mixed them up, shook vigorously, tossed it all up and watched where the pieces landed. As is in life, each piece affected those around it. I wandered along the generally linear processions of image conception and subsequent creation. Again and again, I tied those lines into knots, shredded them, and observed where pieces fell. Repeating similar steps over and over, getting spectacularly different results every time, just like a madman would rightly expect. After making and erasing 120 or so 1/6th plate images, upon emergence of the final three skull plates below, as suddenly as the push for work came over previously, me a new feeling set in. As if through a cracked door, I now saw a way toward new potentials within syntaxes of my own image making, and that of the very daguerreotype process itself, and knew that I needed to step back and regroup. Leaving all those experiments unpublished, I felt the need for collected reflection. Before moving on, further input of happenstance impetus was needed to strengthen my arsenal, and this ingredient of creativity mustn’t be rushed.

Last three 1/6th plate studies

To take a pause, I decided to go make daguerreotypes of the Grand Canyon, as the abundance of nature has never failed to awe me. In preparation for that trip, I purchased a newly invented piece of daguerreotype equipment, a mercury developing apparatus, which promised to make location part of this endeavor safer and easier. In a rush to experience the splendor of Grand Canyon muffled by snow, I didn’t test my new acquisition prior to heading out, and so things didn’t work out quite as well as I had hoped for. Upon return, and with guidance from the inventor, I set out to do another series of tests, this time to see what it is that may be impeding good results while using this new gadget. I again found myself making at least two plates daily for the next few weeks. A series of fuming tests was proposed, and I faithfully executed them day in and day out, but to no avail. This repetitive fuming did something very positive though. I’m sure this has happened to others; we work so hard on something that it consumes all our daily thinking. Those projects tend to seep into dreams and reflect themselves in waking moments when, for just a split second, we let our minds interpret reality by free association. And so I saw clouds of fumes in my dreams and out of my peripheral vision while awake. I dreamed that photography floats amid clouds, and I’m chasing it, and I’m not sure which way is up or even what planet I’m on.

It was at that time that a certain image came into existence. I didn’t know it at the time, but it was the first of what would become Part II of Daguerrean Dream series. One day by chance, I glanced at a broken shutter lying upon a white sheet on my desk. For that split second saw in it a piece of myself; a refugee of a world past, exploring unknown foggy atmosphere in search of safe respite. I thought about old tools, which were so useful and beloved, and how many of them are now lost, defunct, or out of style. I thought about what it meant for technology to perpetually move on. Does this perpetual motion ensure actual net positive gain, or does it doom simple yet perfect methods to being overcome by new and novel, but not necessarily better ways? Daguerreotype method has been with us for 180 years, and at this point it is a novelty process practiced in any meaningful way by less than a few dozen people on Earth. Yet I have never seen a finer singular object-image in front of me, and I’ve looked far and wide. When, after 25 years of expressing myself via photography, I discovered daguerreotypes for myself, it was a life changing experience. It was as if a strange and beautiful alien ship landed inside my brain, bringing with it an unheard language, which sounds instantly made sense. This lonely shutter on a white surface now seemed like a starship, searching for unique appreciation, or perhaps to shuttle me to a more honest place. I envisioned other antiquated pieces of past technologies that were doing the same. I set out to find those pieces, and to create inviting worlds for them to approach and explore, and perhaps to call home.

Searching for imaginary space ships among the post-industrial rubble is not an easy task, involving a mix of patience, intuition, and a good dose of luck, so this was to be a protracted affair. In the meantime, by midsummer 2019, I felt it was time to start revisiting ideas conceived during previous year’s experiments. The skull, having been the subject for my last plates at that time, was now to be the starting point. The dance of Shiva, with its constant cycle of death and rebirth, gave me a vision of this lifeless skull flanked by caviar-like glowing seeds, with geometric shapes searching for order where there may not be any, the Great Void constantly closing in.

This skull image didn’t make it into the final cut for Daguerran Dream series, but it’s one of the more important plates connected to creation of this series. Working on it for well over a week in order to get it just right, gave a chance for a lot of previous ideas to come together in ways I hadn’t expected. I then found myself in the darkroom nearly daily for a couple of months, feverishly working on one plate after the next, and once in a while still taking time to track down my imaginary space ships one by one. I continued to keep my work unpublished, waiting to see where it was taking me.

Clearing all preconceptions of what may appear on my next plate, I worked into November, a year after the journey began. Good images started to add up. Each plate was like a miniature dream; conceived deep within subliminal spaces of my mind, and materialized as if from nothing. These dreams now looked up at me with their own undeniably tangible nature. All the repetitive buffing and fuming started to again dominate my experience of reality and dreams, providing a wonderfully cohesive texture that tied the two together. It is at this point that formulation of this series in its entirety finally coalesced.

After some soul searching and reviewing both work already completed and inspiration present at the time, I decided upon the following format. Daguerrean Dream was to be the name for this body of work, and, it was to consist of several distinct parts, in order to better guide the viewer on the path of discovery. Having 4 parts would follow a classic symphonic format, for I saw this work as an ode to my love of self-expression through Photographic Art, and a hymn to contain those limitlessly beautiful potentials of Daguerreotype method that until now remained mainly dormant. Along with delving into their own distinct uncharted territories, each of those parts was also to be reflective of a particular stage of my life. Experiments that led up to this work started when I was 42, and I knew I would be 43 by the time it was done, so there were to be 42 main body plates, plus one cover image.

What was to become the cover image actually has already come into existence about three months earlier, on August 11th, 2019. That day I found my muse within the brilliant, radiant sun, while soaking up its glory on the roof behind my darkroom. I saw myself holding the Sun in my hand, and its powerful rays were shining simultaneously on all places and peoples. Layers of make-believe lens flare orbs float and shimmer, while my head is thoroughly lodged in stylized clouds, in which I found myself daydreaming ever since I can recall.

As mentioned, I started my explorations long prior to conceptually solidifying this series in its final state. When I saw it coming to fruition, I knew that in order to make sense of it all I needed to step quite a ways back, to the very baseline potential of syntax in which daguerreotype plates were used to communicate. The break with tradition of both my usual ways of working and previous use of this process was so abrupt and wide, that it needed an introduction. It is as if a newly invented instrument is being added into an orchestra, and, as a hello, preforms a quick solo, running through its scales and showing off a few possible choice combinations.

The reader is probably familiar with frustration of trying to explain your dreams to someone else. Even if the dream was very vivid and clear, things that happen there will always be infinitely more clear to you than to someone trying to infer them from a mere description of your vision. This barrier led me to make the first part of this series be as simple as possible. There are 9 plates in this first part, and I was just about nine years old when I felt a draw to learn the noble art of photography in order to express my fascination with existence through it. Before that age, it was as if prior to hearing the full song, I was picking up and learning it one seemingly unrelated chord at a time, trusting it will all fit somehow. New ideas presented themselves at that time almost daily, and it was through them that my view of the world was shaped. Simple as some ideas may appear, when coalesced with others in dynamic ways, wonderful interactions often emerge. If we pay attention to them, we gain a better relationship with ourselves, and our surroundings.

Part II was to be devoted to my beloved space ships. Seven of them were now soaring through unreal worlds, free from constraints of gravity, and independent of this fast and furious world where they no longer found themselves needed. Oh the countless days in school that I spent staring out the window, daydreaming, wishing I could fly. 10-16 was a time of angst and suppressed creativity, so I decided to redeem each of those years with a space ship. One spaceship is an old radio tube, another is an ink pen nib, a third one emerged from insides of a mechanical pencil sharpener. All of these things served as ground for mental escape during my childhood.

Part III is largest of the series. It starts from plate seventeen, since it was a month before turning seventeen that I immigrated to the US from Russia with my family as refugees. A move between such drastically different cultures and at such an impressionable stage of human development is apt to create quite a shock. At first I could barely tie a sentence together, and was even worse at understanding fluently spoken English. Every interaction or task presented a mix of challenges and learning opportunities, each being unique and drastically different. Varied nature of plates in PART III of the series is meant to reflect this life in the New World. Plates in this part are more independent of each other. They stand as separate lessons that add up in background of one’s memory. Some deal with the way our world intrigues my eyes daily in new and unexpected ways. Others address times of pure fantasy, mostly removed from reality, with only a hint of presence of me or of natural world.

Part IV, the last 10 plates of the series, represents the ten years I’ve spent as an independent artist, surviving solely on that work. It was in 2011 that I realized a vision I had since 1997; getting a full size bus and converting it to have a traveling darkroom and presentation area, and so The Photo Palace Bus was born. The idea for Photo Palace was literally a daydream come true, and it was the strongest such manifestation in my life up to this point, but how did all the other nightly forays into dreamland affect me while I was living and learning the path of life?

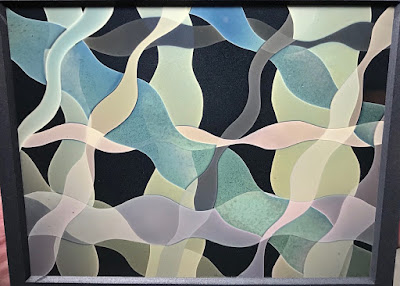

While working with that dream, these last ten years felt most cohesive and focused thus far. In keeping with this continuum, last ten plates are visually tied together. Day after day we follow along the line of our experience in this physical world, with its myriad distractions of things and our possessions, which seem to give us a sense of continuity. We learn from past experiences, and adapt to new situations, in order to better interpret future events and people we meet. At the very base of all those experiences, feelings, memories, and emotions is our wonderfully complex brain. All that we think and all that we identify ourselves as is stored and mixed within the neural network of our brains. Electrical impulses interact with chemical compounds to recollect memories of things we own that remind us of stages of our past. This familiar continuum of material things acts to unify our perception of what we call our life path. However, those same neurons and chemicals that act to tell us that we graduated college or had a burger, at times of sleep provide us with sometimes most vivid and marvelous dreams, some of which will feel just as real as that burger. I wanted this last part to have all plates be connected by real artifacts from my life. Each plate also had to have a crude interpretation of a real-life dream I had at one point or another. All this imagery had to be interconnected, like reality and dreams comingle within memory clouds of our minds.

Putting all of this down in visual format was not an easy task. After envisioning this idea, and then being stubbornly set on it in the face of all kinds of obstacles, it took me a few months to conceive and develop the necessary technique. Once work began though, it didn’t take more than a month, and by end of July 2020 I had all ten secured.

When the last plate of Part IV was done, and all 43 plates were looking back at me, I realized I needed to give these plates the noble secure storage they deserve, so I contacted a kind and qualified woodworker in Canada. Under my loose guidance as far as general feel and particular function, he constructed a gorgeous custom hard wood box, with 42 velvet-lined slots, and a place within the lid to separately display cover plate.

As usual, I’ll remind the reader that any effort to view a daguerreotype in a still form and upon a device screen is at best akin to attempting to smell a rose in a gas mask. These unique objects demand proper lighting, and for absolute truest experience must be held in viewer’s hand. Each daguerreotype will have a nearly infinite array of looks, where colors and contrast will shift and play as one changes lighting and viewing angles. Presented here are but snippets of each plate’s actual range; think of it as hearing one note of a melody, though I did try to choose a good note. I am always glad to present an opportunity for willing parties to see these and other works live at my studio while visiting sunny San Diego, and welcome inquiries about possible purchases, commissions, or exhibitions.

Thank you,

Anton