The Photo Palace

Work via daguerreotype, wet plate collodion, and other 19th century analog photographic methods. Photo Palace Bus is a 35ft traveling darkroom, which brings photography to people. A studio, located in San Diego, is also available for sittings and classes.

Tuesday, September 9, 2025

More Work On Solid Silver Plates, Daguerreian Dreamscape Series Initiation And More

Thursday, April 24, 2025

200 Daguerreotypes In Two Months, One Silver Plate's Adventures

Earlier this year, I've decided to restart my daguerreotype work with a new passion. There is still so much more beauty hidden in plain sight within this noble technique, and to find and rouse that beauty is my ultimate goal. Since the completion of the Chess Series in 2022, the only meaningful daguerreotypes I produced were the ones of the Total Solar Eclipse in Aprif of 2024. I was growing rusty, and I knew it. So, in the last 55 days, I went into overdrive mode and made approximately 215 daguerreotype images, and below is a brief account of those activities.

I estimated that in order to get my image quality back to where I would be happy with, I would have to make at least a hundred images, and quite possibly more. This daunting perspective got me thinking foremost of the financial aspect of making that many plates. And in fact, for the past three years, it was indeed this fiscal barrier that kept me from restarting my experiments in opalescence, and induced my prolonged break. I won't bore the reader with details of various electroplating suppliers and options one could chose with them, or with my thoughts on clad vs. plated silver, or with approximations of how many times on average one can erase a daguerreotype image upon different plates before they have to be discarded. As of today the cost of a single 4x5in plate ranges at about US$100-130, and I will omit here a long tangent about the possibility of electroplating on your own, which in theory could save some money if not time. I figured though, that even with a very high estimate of me being able to make an erase maybe 15 images per plate (though in reality some plates are more like 3-4 times, others 7-10), it would cost me at the very least $2000-2500 to make 300 images..

After putting my thinking cap on, I went a different way. Instead of dealing with going through silver on plate after plate and watching $100 at a time go into the waste bin, I decided to buy a solid 99.9% silver plate. There is an artist in China working on solid silver plates, and I did ask him for advice on this, unfortunately I never did hear back from him. Rio Grande is the only supplier that I have found in the US that sells solid silver in sheets (great monopoly to have, eh). They do have a very decent selection though, and much more experimenting is still possible, but for now I decided to buy what I thought would be the best strength and thickness. It took me a while to talk myself into this expense, but the only other option was buying 200 or so plates elsewhere, only to have them all erased down to copper during my future certain trials and tribulations.

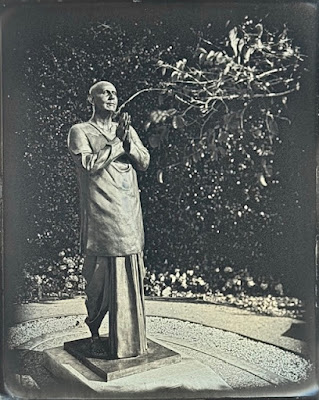

I settled on 18 gauge (~1.02mm thick) quarter hard stock. Unfortunately that stock comes only in 12in width, and it is cut lengthwise to order. I bought a 12x5in strip, and paid right around $650 for it, which, after some careful cutting, gave me three 4x5in plates at just about $220 each. I put one plate aside, and it remains still untouched, with original brushed matte finish it came with. Upon the second plate I made a fun image that I very much enjoy, which will likely not be erased as it may end up in an upcoming exhibit, and then it would be a true shame to erase it even if it's not purchased. The third plate however was facing my full wrath, which I unleashed with full fury.

For once in my life I could make images and not think of the cost while erasing image after image. It was truly liberating and addictive. At first I set out to make one or two images per day. After a few days though it became clear to me that I that pace was not sufficient and I upped it to a minimum of three daily. I have not missed a day since February 28th, and several days up to nine images were made and immediately erased. As I was going, I placed each fixed and dried image on my copy stand and quickly copied it using my phone camera. Yesterday I added image 200 to that album, and so today is the first day in almost two months that I'm not taking a break from polishing and fuming.

As I mentioned above, I knew things weren't gonna go smoothly as soon as I picked up the polisher again. There are many aspects of daguerreotype practice that are not exactly like riding a bike, and so I predicted setbacks in my quest to get quality and consistency of my images to be where I wanted. My first problem though was of such peculiar nature that it literally took me almost all of the first 100 images to narrow down and eliminate. After that issue was gone, of course others remained, but they were slowly improved upon, and now, after 200+ plates, I'm finally feeling like my bearings are somewhat regained. The final battle of course is the one against the army of black spots, but I will always remember what the late and truly great Irving Pobboravsky told me on this subject, that "without some spots it's not a true daguerreotype". I'm still gonna try to keep them in check though, for Irving too.

After the main seemed to have been resolved, I did have some fun playing with the range of tone that daguerreotypes can yield, and below are examples of some of the images that only existed for brief moments. Some are nothing special, while a few I did feel rather sad while erasing. Do pardon the poor quality of these copies, they are but my reference photos of exposures and fuming variations, and are were never meant to be seen as much more than that. The only editing done to images below was done in the standard iPhone Photos app, and was aimed at getting the picture to look as closely to what I was seeing on the plate in terms of brightness and tone.

And how is our single solid silver plate after all this use an abuse? It's just fine and dandy, thank you very much! I recall there having been at least 4-5 images that I simply forgot to copy, maybe as many that failed to such a degree that I couldn't even learn from them and so chose not to copy those, and maybe another few times when something went awry during the fuming stage, and so I had to polish off that deposit of iodides and bromides. So, all in all this one plate I was working with went through at l least 215 polish backs! I carefully measured the untouched control plate, and found that my cutting was unusually precise, and that the still unused plate was exactly the same width and length as the one I was using. After weighing them both, I found that after 200+ polish-backs the plate I'm working with lost only 4 grams! Unpolished plate weighed in at 134.72g, and the used one was 130.62. Originally my calculations were as follows. I figured that with each polishing I must take off at least 2 micrometers worth of silver in order to get the image erased thoroughly enough for it not to come up as a ghost in the next shot. there are 1000 micrometers in 1mm, but of course you can't just erase the plate into thin air, at some point it will become so thin that it will bend. I figured I could take my 1.02mm plate to maybe 0.6mm or if I'm lucky to 0.5mm before it's too thin to work with. This would have given me let's say 500 micrometers to work with, so 250 images. That was my projection. I was wrong though. Maybe 2mic is what one needs to take off once the image has been gilded, and of all the images I made I only gilded 4-5 of them, so I'm probably erasing less than 1mic every time that I'm taking off a non-gilded shot. Knowing that I'm missing 4g out of 134 leaves me to follow the following conclusion. Taking the plate down from 1mm thickness to 0.9mm should reduce it's weight by 10%, which is 13.4g. The 215 erasures I've performed only lost 4g, so I there's still over 9 grams to go, so another 500 ungilded images just to get it to to 0.9mm, and I don't intend to stop there.

I will use this plate for all my upcoming experiments, and will see how many hundreds of images it will hold before it's no longer workable. As the plate gets thinner and thinner, I will finally be able to see what thinner gauges of silver sheets I can get in the future and not have them be too flimsy to work with. For now, I think I'm safe in saying that if you want to try this and want to get a slightly cheaper plate, 20 gauge quarter hard silver sheet should work just fine, as it's only 0.2mm thinner, and I think it won't bend too easily. Then again, that depends on individual polishing methods, and that's an entirely different topic. After a few days break, I'm planning to get back to using this plate over and over again, in search of something truly new and beautiful. Once I feel I'm on the right track, I'll use my regular electroplated plates to hopefully capture some images worth keeping. It is truly freeing though to work with a solid silver plate and to have zero worries about seeing first signs of copper peeking through every time I pick up the buffing materials. Seems to be a reasonable thing to do.

Onward, to new and exciting discoveries my friends!

Anton

Tuesday, February 11, 2025

Wet Collodion April 8th 2024 Total Eclipse - Lithographic Gelatin Silver Final Printing

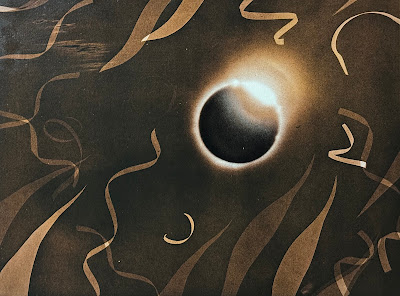

Last April I embarked on a mission, which took me all the way to Alton, Missouri. The goal was to see if I could capture the total solar eclipse with both daguerreotype and wet collodion mediums, while having no specialized equipment and with no assistants either. The journey and it's fruits are described HERE, with finished daguerreotypes can be seen HERE. Having miraculously secured a 4x5in wet collodion negative of the diamond ring moment of sun's reemergence, I chose to make two editions of prints on vintage gelatin silver paper and using lithographic developer, in order to add even more serendipity to the process.

First printing focused solely and squarely upon the conjunction of sun and moon, centered and enlarged to almost fill the page. It then took me some months to process what I wanted to see in the second edition. I won't bore the reader with repeating what fun lith printing with gelatin silver paper is, as one can find that info in my post about the first round of images, but I decided to stick with that, as well as to continue using vintage photo papers like Kodak's Ektalure and Fine Art, Luminos Charcoal R, and others, but this time I only made prints in 11x14 and 16x20 format, forgoing 8x10 altogether.

With this second and final edition, I wanted to more personally convey my experience of the eclipse and the emotions that those 3.5 minutes so strongly evoked. I recall being awestruck at the surreal nature of what was happening, with day turning into night and colors fading before my very eyes. It seemed like reality glitched for a second, and the sky became host to a most amusing and abstract art installation, a fleeting performance by nature of it's best time sensitive installation. I was also overwhelmed by Nature that was happening all around me. Not only were celestial bodies lined up in most peculiar and perfect ways, but I was also in the depth of a lush forest, an environment I thoroughly enjoy. Below are some examples of 11x14 and 16x20in prints that were completed recently. With 11x14in I decided to give a nod to Man Ray and the abstract movement of his time, with somewhat organic shapes mysteriously appearing in random manner in what is usually a clear sky. In 16x20in images, those shapes are replaced with plant material, and in a way I hear them faintly whispering of work by Anna Atkins and William Henry Fox Talbot. As with the first edition, each print was selectively bleached and selenium toned.

Above prints are available for purchase, feel free to use the email mentioned in contact page her to send an inquiry. Printing of this negative is now done forever, as I placed a thick layer of varnish on it. That varnish contains a myriad dust particles, large and small, so the negative itself is preserved, but basically unprintable. I'm elated to have completed this project and to have already sold a few prints from both first and second edition. My art is my only source of income, and sales allow me not only to survive, but to dream of new heights to achieve within the medium I love so dearly.

Anton

Sunday, October 27, 2024

Brief Wet Collodion Adventure - Some Tintypes of the Southern US

Not long ago, I embarked upon a quick trip to some parts of the country I haven't explored yet, and, naturally, I carried a wet plate setup with me to see what sights inspire me to make some tintypes. This trip was actually mainly concentrated on daguerreotypes, both historic and modern, but in this post I'll stick solely to collodion, with an additional historical treat at the end.

My objective was to explore a little bit of the gulf coast, and visit Baton Rouge, New Orleans, Biloxi, and Mobile, along with a few National Parks that can be found in Texas on the way back home. The first plates on this journey were made right after I crossed the mighty Mississippi, in Baton Rouge. I stopped for a bit of a hike along the river, and noticed the overabundance of white, sun-bleached shells that lined the shoreline in all directions. After finding a shady place to park, as it was about 90F at the time, I first decided to make a plate featuring both the shells and the vast bridge I just crossed. A 90mm Nikkor lens was used to achieve this with satisfactory, to me, results. For the second plate, an 8in 1857 C. C. Harrison Petzval was used in order to throw the focus off a bit, and emphasize some of the blades of grass on the hill alongside rivers edge.